Ethereum VM impl from scratch in Rust

TL/DR: solenoid - lightweight, async-first, WASM-friendly Ethereum VM implementation in Rust. ~6800 lines of code, processes real mainnet blocks, runs in a browser. Try it live!

Why

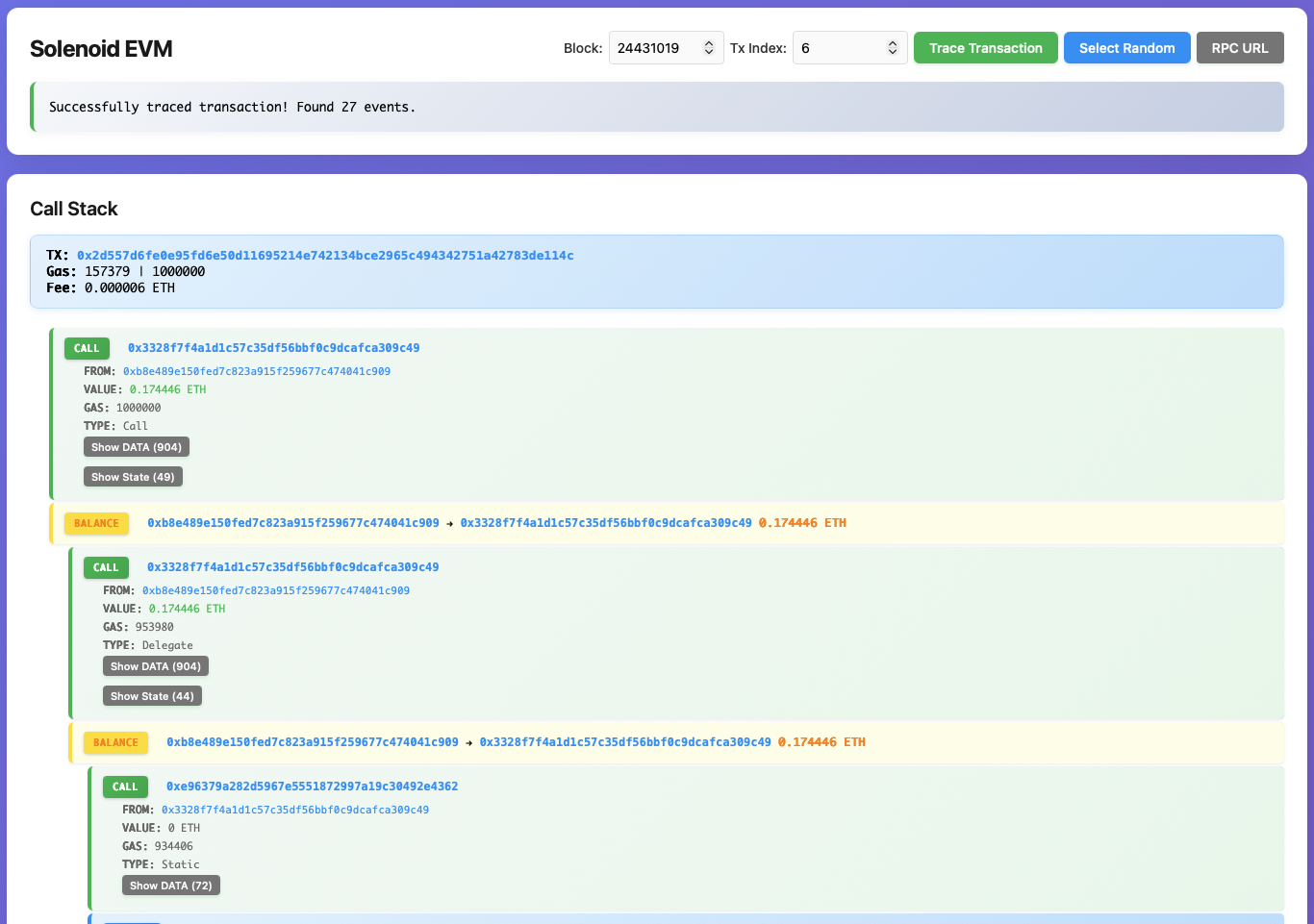

(source: screenshot of solenoid tracing mainnet transaction in a browser)

(source: screenshot of solenoid tracing mainnet transaction in a browser)

After spending more than a year working on Beerus and having to deal with blockifier/sequencer/cairo-vm for Starknet execution, I wanted to understand the Ethereum VM deeply - not from the documentation or someone else’s code, but by building one myself from scratch. The idea was simple: take the Yellow Paper, implement every opcode, make it async, make it compile to WASM, and validate against real mainnet data.

I also had a practical itch: existing EVMs like geth and reth are synchronous, stateful, and definitely not WASM-friendly. REVM is better but still not async and not trivially embeddable in a browser. I wanted something I could use as a library: async state loading, WASM-native, and small enough to understand end-to-end.

Architecture

The whole thing fits into 9 modules:

src/

executor.rs # The big one: opcode dispatch, ~2900 lines

solenoid.rs # High-level builder API

ext.rs # External state: accounts, storage, RPC

precompiles.rs # ecrecover, SHA256, BN128, KZG, etc.

decoder.rs # Bytecode -> instructions + jump table

opcodes.rs # Opcode table (all 256)

tracer.rs # Execution event tracing

eth.rs # JSON-RPC client

common/ # Word (U256), Address, Block, Hash

The design principle was to keep state external to the execution engine. The Ext struct holds all blockchain state and lazily fetches it from an Ethereum RPC node on demand. This makes the whole thing naturally async - every SLOAD, BALANCE, EXTCODESIZE might be a network call, and thanks to Rust’s async/await that’s completely transparent to the execution loop.

How it works

The core execution loop is straightforward: decode bytecode into instructions, build a jump table for JUMPDEST targets, then loop through instructions one by one. Each opcode pops its operands from the stack, does its thing, and pushes the result back.

while !evm.stopped && evm.pc < code.instructions.len() {

let instruction = &code.instructions[evm.pc];

match self

.execute_instruction(code, call, evm, ext, ctx, instruction)

.await

{

Ok(StepResult::Ok(cost)) => {

evm.gas(cost)?;

}

Ok(StepResult::Halt(cost)) => {

evm.stopped = true;

evm.reverted = true;

}

Err(_) => {

evm.stopped = true;

evm.reverted = true;

}

}

// ...

}

Every instruction returns a StepResult carrying its gas cost. The Gas struct tracks limits, usage, and refunds:

pub struct Gas {

pub limit: i64,

pub used: i64,

pub refund: i64,

}

impl Gas {

pub fn finalized(&self, call_cost: i64, reverted: bool) -> i64 {

if reverted {

self.used + call_cost

} else {

let used = self.used + call_cost;

let cap = self.refund.min(used / 5);

used.saturating_sub(cap)

}

}

}

The refund cap at 1/5 of used gas is per EIP-3529 (London). Getting gas accounting right was by far the most time-consuming part of the project - not because any single rule is hard, but because there are dozens of them interacting together, and they must all be exact to match mainnet.

State management

The Ext struct is the external world from the EVM’s perspective. It holds account state and lazily fetches from an RPC node:

pub struct Ext {

remote: Option<Remote>,

pub state: HashMap<Address, Account>,

pub original: HashMap<(Address, Word), Word>,

pub transient: HashMap<(Address, Word), Word>,

pub accessed_addresses: HashSet<Address>,

pub accessed_storage: HashSet<(Address, Word)>,

// ...

}

When the EVM reads storage that hasn’t been seen yet, Ext makes an RPC call to fetch it. The original map tracks storage values at transaction start (needed for EIP-2200 gas calculation on SSTORE). The transient map is EIP-1153 transient storage. The accessed_* sets are EIP-2929 warm/cold access tracking.

One important design choice: every state modification is recorded as an AccountTouch:

pub enum AccountTouch {

WarmUp(Address),

FeePay(Address, Word, Word),

GetState(Address, Word, Word, bool),

SetState(Address, Word, Word, Word, bool),

SetNonce(Address, u64, u64),

SetValue(Address, Word, Word),

Create(Address, Word, Word, Vec<u8>, Word),

// ...

}

This is what makes revert work correctly. When a call reverts, we walk the touches in reverse and undo each one. The survives_revert method determines which touches persist through a revert (read-only operations and fee payments). Getting this right was crucial for matching REVM’s state diffs.

The high-level API

The Solenoid struct provides a builder pattern for constructing and executing transactions:

let result = Solenoid::new()

.execute(contract_address, "methodName(uint256)", &args)

.with_header(header)

.with_sender(sender)

.with_gas(Word::from(1_000_000))

.ready()

.apply(&mut ext)

.await?;

The method selector (first 4 bytes of keccak256(signature)) is computed automatically. For contract deployment, use create() instead of execute(). For plain ETH transfers, use transfer().

Gas: the real boss fight

If someone told me before I started that most of the complexity in the EVM is in gas accounting rather than in opcode logic, I would not have believed them. But it’s true. The actual opcode implementations are usually straightforward - ADD pops two values, adds them, pushes the result. The tricky part is knowing how much gas each operation costs, and the rules are anything but simple.

EIP-2929 divides account and storage access into “warm” (100 gas) and “cold” (2600 gas) categories. First access in a transaction is cold, subsequent accesses are warm. Then EIP-3651 says coinbase should be pre-warmed. And the access list from EIP-2930 pre-warms specific addresses and storage slots at a cost of 2400 per address + 1900 per slot.

SSTORE gas rules alone (EIP-2200 + EIP-3529) are a small state machine: the cost depends on whether the slot is being set to its original value, set from zero to non-zero, set from non-zero to zero, or set from non-zero to a different non-zero, and whether it was already accessed in this transaction. Then there are refunds for clearing storage, but capped at 1/5 of total gas used. Memory expansion costs are quadratic. CALL stipend rules change depending on whether value is being transferred.

Getting all of this exactly right is what takes the time. The opcodes themselves are the easy part.

Validating against REVM

To validate correctness, solenoid’s runner example processes full mainnet blocks and compares every transaction against REVM - opcode-by-opcode traces, gas used, return data, reverted status, and post-transaction state diffs:

$ cargo run --release --example runner -- 23624962

...

📦 Fetched block number: 23624962 [with 129 txs]

(total: 129, matched: 129, invalid: 0)

When a mismatch is found, both trace logs and state snapshots are dumped to files for side-by-side analysis. This was the workflow for most of the development: run a block, find the first mismatch, stare at traces, fix the bug, repeat.

The rpc-proxy crate helps here - it’s a caching HTTP proxy that stores RPC responses locally, so replaying blocks doesn’t hammer the RPC provider.

Precompiled contracts

Ethereum has 10 precompiled contracts at addresses 0x01 through 0x0a. These handle operations that would be prohibitively expensive in EVM bytecode: elliptic curve operations, hashing, modular exponentiation, and KZG point evaluation (EIP-4844).

The most involved ones are the BN128 (alt_bn128) pairing and addition operations needed for zkSNARK verification, and the BLS12-381 precompiles. For these I used arkworks-rs, which was already familiar territory.

WASM support

Compiling to WASM was one of the original goals and it works out of the box:

cd wasm-demo/

wasm-pack build --target web

The key enabler is the async-first design. In a browser, there is no multi-threaded tokio runtime - but that’s fine, because all state lookups go through async .await points, and the single-threaded tokio runtime works perfectly in WASM. The conditional compilation handles the differences:

[target.'cfg(not(target_arch = "wasm32"))'.dependencies]

tokio = { version = "1", features = ["macros", "rt-multi-thread"] }

[target.'cfg(target_arch = "wasm32")'.dependencies]

tokio = { version = "1", features = ["macros", "rt"] }

After fighting with WASM compilation for Beerus (which required patching 4 external dependencies), making solenoid WASM-compatible from day one was a deliberate choice. No Rc where Arc is needed, no usize where u64 is meant, no file I/O in the hot path.

Uniswap V3 as a smoke test

A good end-to-end smoke test is calling Uniswap V3 QuoterV2 - it exercises deep call stacks, complex storage access patterns, and non-trivial math:

$ cargo run --release --example quoter-sole

...

📊 QuoterV2 Results:

💰 Amount Out: 1 WETH for 3943.532812 USDC

📊 Price After (WETH/USDC): 3955.222269012662

🎯 Initialized Ticks Crossed: 1

⛽ Gas Estimate: 84919

✅ Transaction executed successfully!

🔄 Reverted: false

⛽ Gas used: 123290

Matching REVM’s output on a complex DeFi contract call was a satisfying milestone.

Execution spec tests

The solenoid-t8n crate contains still-work-in-progress implementation of the t8n (transition) tool interface expected by ethereum/execution-spec-tests. When completed, this will allow running Ethereum’s official test suite directly against solenoid:

uv run fill tests/ \

--evm-bin=../target/release/solenoid-t8n \

--fork=Cancun

What I learned

Building an EVM from scratch is an excellent way to learn Ethereum’s internals. Some things that became obvious only through implementation:

- Gas accounting is the hard part, not opcode logic.

SSTOREgas rules alone could be a blog post. - The EVM is fundamentally a stack machine with 256-bit words, but the “simple” design hides enormous complexity in the edges: memory expansion costs, call stipends, code deposit limits, the 63/64ths rule for forwarding gas to calls.

- Async-first design pays off. Making the state interface async from day one means WASM compatibility comes almost for free.

- REVM is an excellent reference implementation. Having a battle-tested EVM to compare against opcode-by-opcode made debugging tractable.

- The hardest bugs to find were off-by-one gas accounting issues. An opcode that charges 2 gas too much cascades into completely different execution paths in nested calls.

The project is at the point where it processes real mainnet blocks with 100% match against REVM on gas, return data, and state diffs. There’s still work to do - EIP-7702 delegation handling needs more attention, and the execution spec tests coverage could be improved - but the core is solid.

Full code: github.com/sergey-melnychuk/solenoid